I looked up in disbelief when I heard her say “I sent my daughter to Duni [a small town 15-20 minutes away] to study for her exams. We have rented a room for her in the town so that she can study without distraction.”

“You sent her there all by herself?” I asked, surprised that the resident of a tiny village in Rajasthan would take such a drastic step going against entrenched social norms against mobility and education of girls. “She is staying with other girls from her college”, the mother replied confidently even as she called to someone to go and deliver milk to her daughter on his way.

Kajori Bai lives in a village 80 km from the nearest city. Until 8 years ago she observed purdah and hesitated in speaking to men. She was married at the age of 11 though allowed to complete schooling until 8th.

Her daughter is studying home science in college. Kajori is not planning to marry her 20 year old daughter just yet, although she already arranged the engagement some years ago, at the time of the older daughter’s wedding. Narbada Bai, who lives in a nearby village also related a similar story concerning her thirteen year old who although engaged is also going to be allowed to finish 12th before being sent to the in-laws.

We met Meera Bai, 25, who convinced her husband to join a nursing course in Ajmer, while she herself works as a trained ‘pashu sakhi’ a para vet in her cluster of villages. She has travelled to Madhya Pradesh and interacted with women there on a trip organized by Srijan, an organization founded by Ashoka Fellow Ved Arya.

Four years into her marriage and she doesn’t have children yet. She says, “My in-laws know the work that I am doing and how important it is. They don’t put pressure any more. We will have children once we can stand on our own feet.” There’s no shy smile as she says this. She speaks confidently and clearly.

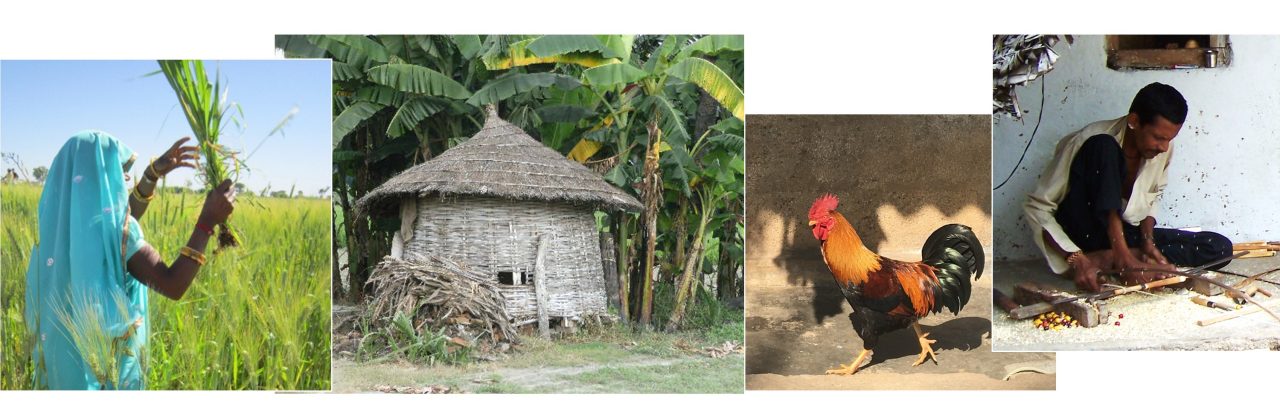

All the women we met were affiliated with Srijan, which works on livelihood programs related to agriculture – cultivation and dairy – leveraging SHGs for creating village level structures and institutions. They work almost exclusively through women. According to Srijan team, when they started working on yield improvement programs for soya with male farmers, they realized that they had to do a lot of repetition and there was no cohesion in the farmer groups. And they realized that much of the farm labor was provided by women. So they started leveraging SHGs for providing information about seed preparation, proper spacing, sowing of soya. It was tough going at first. It was difficult to convince people that if you plant only half as many seeds, your yield will be 20% higher. But when one or two women tried it out on one ‘bigha’ of land and compared the yield, more women joined.

In milk collection, they also relied on SHG model for dissemination of good practices in care of milch animals. And later launched an all woman pashu sakhi (para vet) program. It seems that mortality of buffaloes was a big issue in the area. With the help of pashu sakhis, who focus on health, hygiene and preventive care of buffaloes and goats, the mortality was reduced to only a single calf perishing in 12 months.

But there was a design behind all of this seemingly “purely” economic activity. The payment for milk deposited at collection centers is only given to the women (they have to come collect it). The receipt for soya deposited at collection centers is issued in the name of women. All records at Srijan are maintained in the womens’ names.

There are many reasons that Srijan, the non-profit founded by Ashoka Fellow Ved Arya, has been able to bring about such change within 8 years of formation of the SHGs. After having visited many such organizations and going through research on these topics, I believe that the reason Srijan has been able to achieve this has to do with the fact that the processes it has designed make it very clear to the women and everyone around them, that the extra income being brought home is due to the work of the household’s women.

The entire trip was one full of surprises. While my colleague and I sat at Kajori Bai’s home discussing her work as SHG Federation president, as an operator of a milk collection center and as a ‘pashu sakhi’ (and many other roles), her mother-in-law quietly swept the courtyard and made tea for us. The father-in-law first sat near us, and then uncertain whether this was meant to be an SHG (therefore women members only) meeting, started moving away. Someone from our meeting group told him that he can stay, it is only a discussion, not an SHG meeting.

When we enquired about Kajori Bai’s schedule for the rest of the day (she’d been with us from 7 in the morning), she said she had 3 more meetings to attend, one related to the SHG Federation, another relating to a visit to another SHG meeting (sort of like an inspection visit) and another in preparation for a PRA to be conducted in a new village where they want to start an SHG. She said that often people visit her with problems at their SHG, where she ends up resolving conflicts and such. Her schedule sounded as busy as any corporate CEO.

At Narbada Bai’s home and farm, we saw her husband sitting to one side and chopping green fodder for buffaloes, while Narbada Bai explained to us how she, an illiterate, keeps track of the dozens of animals under her care, as the village ‘pashu sakhi’.

At another household where we met soya farmers, the husband patiently hovered and waited during our discussion with about a dozen women, occasionally hovering but never interfering with his own ideas. Only once our discussion was over, he came across and sat down and started telling us about some of the services he provides to villagers as a Srijan service provider.

While all households might not be as emancipated as the three we visited, it is clear that these changes could not have been brought about if Srijan had followed more expedient ways of working. It may have improved incomes for these families, but the processes, the new ways of thinking about agriculture, more scientific cultivation practices, and certainly the societal change relating to women’s stature would not have been possible.

One can only hope that now that the villagers understand a woman’s contribution to household and society, the next time a woman’s second child is also a baby girl she won’t name her Naraji (“upset”, as in “the gods are upset with us”) whom we met, or Mat-de Ram (“don’t give, Ram” as in “don’t give us more girls, god”) whom we heard about.